This is my 25th Letter from the Questhouse, and I am so grateful for the joy this practice has afforded me, for the time and space I’ve had to write this year, for Damien’s crackerjack editorial skills, and, most especially, for the surprising and wonderful ways this project has connected me to you all.

Last year, when I started QH, I was looking for a goal of the right size - large enough to challenge me, but modest and clearly defined enough to manage. The trickster years of the pandemic taught us all how vulnerable we are to circumstance, and so I entered into this contract with some trepidation.

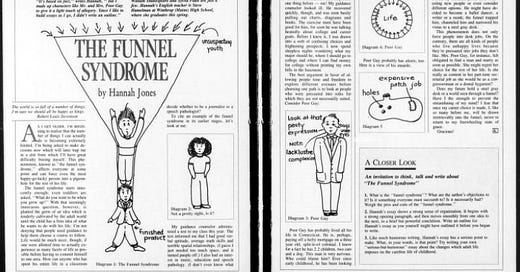

A deeper anxiety was at play, too, as it is whenever I set a writing goal. Ever since high school, when I won a national writing contest and publication in Literary Cavalcade (a Scholastic classroom magazine for high school students), my relationship with writing has been fraught. Getting pegged as a gifted kid, without also receiving guidance about how to put those gifts to practical use, led to decades of frustration and self-loathing. My mind was so full of wrongheaded beliefs and exhausting baggage about writers and writing that, even though it was the professional goal I cared most about, I couldn’t figure out how to get anywhere with it.

It didn’t help that Scholastic made a big deal about all the famous authors who had won their writing awards in past years, among them Joyce Carol Oates, Truman Capote, Stephen King, and Sylvia Plath.

As a kid, I fell in love with the special feelings writing gave me: the quiet delight of inhabiting a world of my own imagining, the thrill of producing a musical sentence, the deep satisfaction of finding the right word, the hunger to be understood. But by the time I graduated high school, those pure motivations were secondary to my desire for the trappings of the role. Instead of writing because I loved it, I fantasized about creating deathless art, of bagging a Big Five publisher, and of becoming famous, because that’s what I thought “being a writer” meant.

At the same time, I was convinced that there were only about a hundred writers who really mattered, and most of them were dead white guys. The rare exceptions, such as my hero Toni Morrison, were demigods blessed with monstrous talents I couldn’t hope to possess. Except that I did, secretly, dream that I might be an undiscovered literary genius. Which made actually sharing - or even sitting down to produce - my imperfect, immature work almost impossible, because it would surely have revealed me as a sham and an imposter. (See Carol Dweck’s work for insight into why you might have hit similar roadblocks in your life.)

When it became clear that I wasn’t going to be a literary child genius, I spent the next couple of decades taking the opposite approach - convincing myself that the mark of a “real” writer is a willingness to toil in happy obscurity, clocking in hours at the desk, tallying words like calories or sit-ups, or any other stat linked to my personal betterment. As a result, I have produced dozens and dozens of notebooks full of prose that I would be horrified for anyone to read, not because it reveals my darkest secrets (though sometimes it does), but it’s every bit as boring as anybody’s unfiltered mind gunk would be.

Over the decades, I have amassed a modest handful of publication credits: a few essays, a couple of education texts I wrote on contract back in my teaching days, and a few articles in small magazines. I have also produced two book-length drafts: a collection of essays called Playing House (the final project for my master’s degree) and a novel, Hero Green. I labored over both of those projects, felt compelled to visit and revisit them, to shape and reshape them so many times that, if the work had been done by hand, my smudged graphite fingerprints and pink eraser marks would blot out the text entirely. Both of those projects reconnected me with my childhood love of writing, but, apart from one published essay from the Playing House collection, I never felt either project was truly finished, and neither of them made me a “real” writer. Letters from the Questhouse did.

I became a writer when I started to show up for an audience. And, for this whole year, you have been my audience. I have managed to hit the “publish” button every two weeks, in sickness and in health, at home or on the road, and whether I felt in the mood or not. I have, by my own lights, finally become a real writer.

Before QH, my audience was really one person: my mom. She taught me to write, and she was always my first reader and editor. She was my lifelong partner in chasing the feelings writing has given me since childhood. I craved her approval; my voice was tuned to her ear (which was not always a great thing: my mom’s ear was tuned to Dickens and Kate Douglas Wiggin, two excellent writers whose respective styles aren’t exactly in vogue these days). I wanted to untangle my most complex ideas, my deepest imaginings, so they made sense to her. She was a compelling audience because she was so moved by beauty. One time, my family went to the Tate Gallery in London, and Mom was so overcome by aesthetic ecstasy that we had to spot her in case she actually fell down. I wanted my words to affect her that way, or at least to make her cry.

For a while, I was quite sorrowful that Mom never got to read Letters from the Questhouse. And then I realized that I never would have written it if she were alive. I wouldn’t have needed to, because telling her a story on the phone or sharing my latest novel idea, or copying her on an essay I had written, would have been enough. Also, frankly, I inherited some of my most broken ideas about what it means to be a writer from her, and she might have viewed this homegrown “publication” as a bit self-indulgent, a belief I constantly have to remind myself isn’t true or fair. Part of the magic of this practice is the regular deadline: I can’t keep laboring over my posts until they’re perfect, because I would never hit the “publish” button, and then what would be the point?

This delightful new vision of what it means to be a writer is fragile, and it fades in and out of focus, sort of the way those 3-D Hidden Image posters do. It’s easy to revert to the bleak, flat binary of success and failure that dogged my days for so long. Even (or especially) praise can do it: sometimes a reader tells me that I should really find a publisher for my essays, that I’m every bit as good as the writers they read in magazines, and I feel the sickly stirrings of parasitic ambition. I am grateful for those kind words, and I am also working hard to hold onto the joy of this practice, even if it means a (much) smaller circle of influence, at least for now.

On the other hand, when I run into an old friend at the grocery store, and he tells me that my words meant something to him, or I receive a text from a reader who wants to continue the conversation she was having in her head with me, or when I count the new friends I have made through Substack, the full 3-D scene pops into view, revealing the wondrous sweep of my fame and fortune.

I’m so grateful to you all.

Hannah my friend, your writing is amazing or should I say “Groovy”💕

Beautiful words, Hannah! I have been struggling with writing for my PhD, and this put so much back in perspective for me. And remembering your mother and many Thanksgivings together as well. A flood of wonderful memories AND helpful advice all rolled into one beautiful essay! Thank you!!