I am really enjoying the first course in my Stanford Continuing Studies Novel Writing Program. My teacher, novelist Rachel Howard, is excellent, and I’m already learning so much.

This week, in addition to six meaty discussion questions, over 100 pages of reading, and feedback posts for two of my classmates, my assignment is to map out all the “lines of tension,” including the “through line” of my book. Though I taught English for 25 years, I had never thought about novels in quite this way, and I am finding the idea both compelling and useful.

Here’s how Rachel describes it in her lecture notes:

…to keep humming through its middle, a novel needs to open lines of tension. Some of these lines of tension will be short lines; that is, some events in the novel will open questions that are tense but relatively quickly answered. These shorter lines of tension are important: They make scenes and chapters crackle with immediacy! But no novel will hold together without also opening up longer lines of tension, and in particular one long line of tension that opens a question at the story's outset that is not answered until the story's peak.

After I have identified the lines of tension in my book, I am to write a list and brief description of every event. (This is terrifying, even though I know that this is the most preliminary of exercises, and I’m not bound to any of these ideas as I draft.) Once I have the list, my next job is to decide how I will dramatize the events. Compelling and important events might have multiple scenes. Less important events might be summarized and not dramatized at all. Finally, I’m to look at which scenes I’m drawn to write first, as anchors for the novel.

So, I’ve been thinking a lot about through lines, in life and in art.

The most compelling lines of tension in my own life have been personal, romantic, or familial. As much as I have always claimed to be a socially engaged and empathetic person who cared about the wider world, I, like most people I know, have centered myself in my life story. Am I lovable? What should I do with my life? What will happen to the people I love? How does it all affect me?

Most of the books and movies I’m drawn to also put individuals at the center. Love stories. Family sagas. Tales of friendship and kinship. We are meant to live vicariously through the individuals at the center of those tales, and one of fiction’s great virtues is supposed to be its ability to put us in another person’s place. But whether it’s an alien life form or the girl next door whose life we inhabit, we are always the same person looking through their eyes.

Some books unfold against the backdrop of societal, political, or ecological crises, but they aren’t really about the crises themselves. Notice what gets the top billing in Love in the Age of Cholera, for example. Disaster movies aren’t, at their hearts, about the disasters, no matter how big the tidal wave or earthquake. We used to call that kind of conflict “Man vs. Nature,” and we were always supposed to side with the Man.*

For about eight years now, my sense of story has been shifting away from that perspective. I’m still selfish and individualistic, but I no longer feel that same main character energy.

After Tr*mp’s election in 2016, as I have written about elsewhere, all of my fantasies were about pushing back against his threat, and they were all centered on my privilege and sense of entitlement. I would move to Canada. Or else my state, California, the fifth largest economy in the world, would threaten to secede from the US (and withdraw its financial support of the nation) unless the US rewrote the Constitution to eliminate the Electoral College and gerrymandering and the imbalances in Senate representation. Or Google would turn off the rest of the country’s Internet, just to show them who was boss. I felt impotent rage about being governed by a monster, and my fantasies were a way to grapple with that powerlessness.

In 2020, Tr*mp’s candidacy, an existential crisis in its own right, occurred against the backdrop of two other existential crises that directly affected me and those I loved: Covid and the California wildfires.

Though it was so clear how global climate chaos contributed to both the fires and the pandemic, I still fantasized about individualistic remedies. I spent the first six weeks of the CZU fires sharing my space with friends, donating to relief efforts, and volunteering. But shortly after the sky turned orange and blotted out the sun, a day of the deepest, most animal dread I have ever felt, I cashed in some of my privilege and retreated to Maine for three months, where I could breathe clean air and hunker down with my family.

Safe in my sister’s spare bedroom, I obsessively researched “smart” places to move to evade the climate crisis (including Asheville, North Carolina, a supposed climate haven). More childish fantasies about personally prevailing against a global threat, even as the daily toll of acres burned and community members killed by Covid stacked the evidence against any chance of separate specialness.

This time, as I hunker down for a third close Presidential contest and sweat out the weeks until the election, it’s much harder to imagine an escape for myself, or anyone I love, or the planet, if Tr*mp wins. Even if he loses in a landslide, and he’s swept off the national stage by our first woman President (which would be so, so great), that’s not really a happy ending. Appalachia is still reeling from Helene, and Milton has Florida in its sights, and it has been so hot and dry here in Northern California that it feels like we could burn down any second, and yet our government spends our tax dollars to bomb babies in Gaza and the West Bank and Lebanon.

We are living through the consequences of seeing ourselves as separate from each other and the planet.

I know that there are helpers everywhere getting food to their communities, sharing their resources, fighting the good fight. This time around, though I have been nobody’s idea of a selfless activist, I have helped a little, too. I’m trying not to feel so separate, though I also haven’t relinquished my privilege, either.

The novel I wrote before this one, allegorically entitled Hero Green is about a young Witch who builds an environmental movement, fights an evil corporation, and, in the process, learns that the world doesn’t actually need more individualistic heroes. Rather, we need to start acting collectively, to behave more like bees or trees or mycelium. Writing the book helped me work through some of my own fantasies about healing the world and to understand the flaw in that design.

In this new book, I’m back to a protagonist whose through line is all about her: her passions, her grievances, her search for meaning. I’m setting the book in 2007 because that’s the era of the housing and banking crises, the year the iPhone came out, the year Facebook blew up.

My character’s selfishness derives, in part, from her exposure to an increasingly toxic late-Capitalist world. After a lifetime of identifying as an integral part of her community and family web - teacher, mother, daughter, wife, neighbor, friend - Norah (my character) begins to resent her own sacrifices and to feel ashamed of her own smallness, in part, because the rest of the world seems to see her traditional values as quaint and a bit pathetic.

I have been, tentatively, calling the book The Perfect Bomb, because I thought my main character was going to blow up her own life. But I’m realizing that the bomb at the heart of her story is the one that’s been ticking louder and louder in America’s psyche, one planted by the serpent’s tale of our separateness.

I’m also realizing that there’s one person who is still very much convinced of his main character energy: D. J. Tr*mp, backed by his army of righteously indignant Christian white nationalists. He is the apotheosis of the Reagan-era philosophy that greed is good, that white men should run the show, that every resource on Earth - human, animal, environmental - is something to be exploited, and women are objects to be used and judged and forced to bear children.

Where did he get that idea? John Locke? The Doctrine of Discovery? The Bible? I don’t know, but I do know I drank from the same cultural well that Tr*mp did (I mean, roughly), and the water is making me sick.

I know, too, that Tr*mp’s obsession with grievance and entitlement appeals to so many people because they are victims of our hollowed out society, too. They genuinely have less now than they did. Less material wealth, less security, less community connection. Their theory about why that’s the case is diametrically opposite mine, but that doesn’t change the fact that we’re in the same boat.

But what I do with that knowledge as a novelist? Does it even make sense to tell a single person’s story in this context?

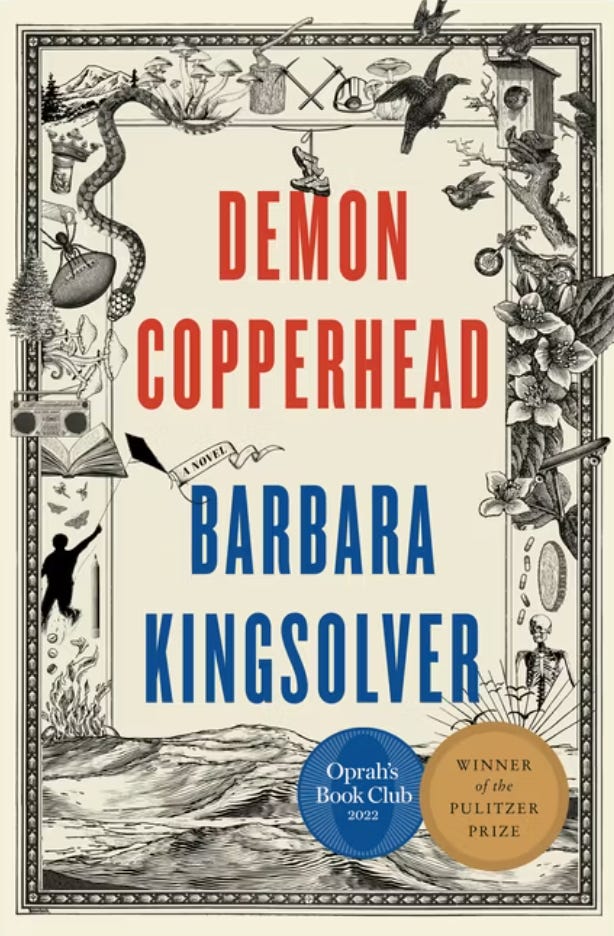

Maybe the answer lies in one of the 21st century’s greatest novels: Demon Copperhead, by Barbara Kingsolver. Kingsolver’s novel centers a young boy who grows up in foster care, whose family and community are torn apart by extractive and exploitative industries (especially the tobacco and opioid industries) that only understand value in capitalistic terms. She depicts a traditional Appalachian society decimated in a couple of short generations, and she also offers hope: an RN who fights the pharmaceutical industry while treating its victims, a pair of teachers who offer their students a nuanced analysis of their society’s place in the world, and Demon Copperhead himself, who battles opioid addiction and creates art that argues for a better world.

Kingsolver’s story helped me to feel a connection to Appalachia, one that hurts my heart as I imagine its destruction under Helene and strengthens my sense of solidarity with people, many of whom may not vote the way I do this November. It teaches me that a character’s through line can be both personal and deeply connected. In fact, healthy people are connected, and writing stories about those people can be an act of resistance.

I’m going to have a hell of a time doing my homework this week, and I can’t wait.

Good morning! I read your latest post with eagerness and curiosity. Your writing is so vivid and the journey you’re on is so relatable. Thank you for the in-depth candor you offer about your class and your writing!

covid was a covert event and we were lied to about so much of it.

A Forensic Arborist has determined that 80 % of these so called 'Wild Fires" were not wild nor natural. This was obvious to many of us who are aware of the fact that Climate Change is being used to tax and eventually control all humans on planet Earth.

Climate changes....and has every millions and millions of years. The oceans have risen and fallen hundreds and hundreds of feet over millennium.

There are shells and whale bones up in Bonny Doon.

These ocean level changes occurred long before there were humans.

What is meant by the Climate Hoax....isnt that climate change doesn't happen but it's not from what they are telling us. Much of it is natural...and then...we have the reality of weather Modification. They have had this technology for decades. They are starting to tell the truth about it...but not that many of these disasters were human created...on purpose. There's an agenda to lower the population AND to corral humans into 15 min cities. That is what these fires are about.

Santa Rosa, Paradise, Lahaina and LA....were not wild or natural fires.